Wildfires and Best Practices for Sharing Household Water Contamination Test Results

Highlights

After a major wildfire, Dr. Gina Solomon, former director of PHI's Achieving Resilient Communities (ARC) and PHI's Science for Toxic Exposure Prevention, along with PHI’s Tracking California program and researchers from UCSF, tested household water samples for chemical contaminants. Dr. Solomon and the team worked to ensure that the study participants and area residents were quickly informed of the test results, felt empowered by the data, and could take meaningful action to protect their health.

87% of study participants said that receiving their test results was useful

87% of study participants had high confidence in the test results

83% of study participants said that the test results were understandable

-

Focus Areas

Environmental Health -

Issues

Population Health, Wildfires & Extreme Heat -

Expertise

Health Education & Promotion, Outreach & Dissemination, Research – Quantitative

Following the Northern California Tubbs Fire in 2017, returning residents complained of strange odors in the drinking water. State and local water authorities tested for hazardous chemicals called volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The tests found VOCs in water distribution pipes, with the VOC benzene, a chemical known to cause cancer and reproductive harm, found in some pipes at more than 1,000 times the maximum level allowed under clean water rules.

So after the 2018 Paradise Fire in California, there was much concern about the safety of the drinking water for the residents of the 1,700 homes that remained standing in and around the Town of Paradise. In a study of the area’s drinking water, under the leadership of Gina Solomon, former director of PHI’s Achieving Resilient Communities (ARC) and PHI’s Science for Toxic Exposure Prevention, and in partnership with PHI’s Tracking California program and researchers from UCSF, teams collected tap water samples from 136 homes in and around Paradise that were still standing and tested the water for over 100 chemicals. The research was supported with an emergency response research grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS).

The research has provided insights about how to prevent serious drinking water contamination after future wildfires, but the team also wanted to ensure that the participants and area residents were quickly informed of the test results, felt empowered by the data, and could take meaningful action to protect their health. This process could potentially mitigate some of the trauma from the wildfire and assist with rebuilding a sense of community and personal agency. Their study, “Returning Individual Tap Water Testing Results to Research Study Participants after a Wildfire Disaster,” details the process they used to get test results back to the individual participants and community members.

Previous studies have acknowledged the importance of sharing research findings with the impacted community and study participants, but there was no previous project to develop a strategic approach to the challenge of quickly developing and distributing individual test results to study participants following an emergency. While moving quickly, the Tracking CA team aimed to ensure that results were conveyed with the appropriate degree of scientific certainty about the potential health implications. They also worked to get test results to participants in culturally and linguistically appropriate ways, and with community input.

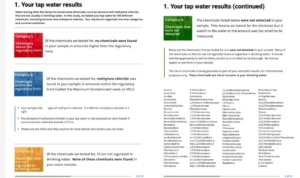

In addition to holding a community meeting to share general, preliminary findings, the team communicated the results in a packet of written materials for each study participant which included the individual test data from their home’s water sample, a three-page frequently asked questions (FAQ) document, and factsheets on commonly-detected contaminants. The reports were developed and designed to be easily understandable, scientifically accurate, and useful to participants. The researchers were sensitive to participants’ anxiety about their water and aimed to return results as quickly as possible without impacting accuracy or clarity. Participants received their individual results less than a month after the testing.

Following the return of the test results, the team surveyed the study participants to get their feedback. The surveys showed that 83% of participants found their test results to be understandable, 87% found them useful, and 87% were confident in the accuracy of the test results. Receiving their results made most participants feel less worried about their drinking water quality, despite the fact that some chemicals were found in most samples. Over one-third of the participants reported taking some kind of action around water usage habits after receiving their tap water sampling results.

This work from the PHI and UCSF “Fire and Water” team provides unique insights for future crisis communication strategies around returning results from disaster research to study participants, including

- providing information in a timely and urgent manner;

- using messaging that is simple, repeated, and factually accurate;

- providing honest information with empathy for those affected by the disaster; and

- being flexible and ready to respond to rapidly changing situations.

PHI’s Child Health and Development Studies program is also developing and testing best practices for reporting study results back to participants. See their work on “Developing Best Practices in Sharing Study Findings with Participants.”

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.