In the News

Extreme Heat is One of the Deadliest Consequences of Climate Change

- Los Angeles Times

-

Focus Areas

Environmental Health -

Issues

Climate Change -

Programs

Tracking California

It was the hottest August on record in California.

For more than three weeks in 2020, back-to-back heat waves settled over the Southwest, claiming dozens of lives and leaving tens of millions of people sweltering in triple-digit temperatures. The days brought suffering and the nights offered little relief. On maps of the record heat, Southern California glowed like an ember, its normally temperate coast shaded orange, its inland cities and desert towns a deep, smoldering purple.

Seventy-three-year-old Jorge Valerio-Santiago went to work on Aug. 20 digging cable trenches at a mobile home park outside Desert Hot Springs in Riverside County. After several hours, he began to feel ill and returned home to a trailer that lacked air conditioning. His nephew found him that evening, lying still in the dirt driveway where he had gone into cardiac arrest. The paramedics pronounced him dead at the scene.

Extreme heat is one of the deadliest consequences of global warming. But in a state that prides itself as a climate leader, California chronically undercounts the death toll and has failed to address the growing threat of heat-related illness and death, according to a Los Angeles Times investigation.

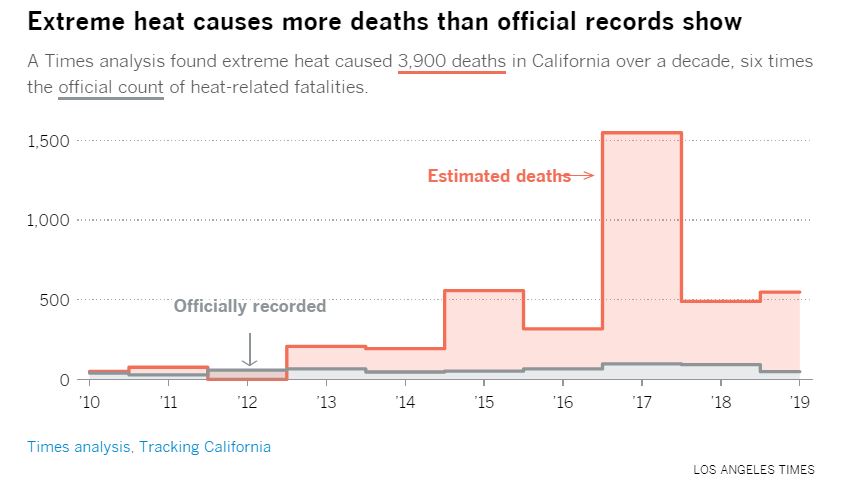

Between 2010 and 2019, the hottest decade on record, California’s official data from death certificates attributed 599 deaths to heat exposure.

But a Times analysis found that the true toll is probably six times higher. An examination of mortality data from this period shows that thousands more people died on extremely hot days than would have been typical during milder weather. All told, the analysis estimates that extreme heat caused about 3,900 deaths.

Experts interviewed by The Times said an effective state response would include identifying and assisting vulnerable populations, and putting in place a surveillance system to track when and where heat-related deaths and injuries are occurring. But the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) doesn’t collect that kind of real-time data. It can’t say how many people died in last year’s heat waves because it does not examine death records during severe heat waves — as authorities in Oregon and Washington did this summer after days of record-breaking temperatures.

In 2013, a group of state agencies, led by the Department of Public Health and California Environmental Protection Agency, issued more than 40 recommendations to prepare for extreme heat. Years later, the state has taken little of its own advice, including that the health department “improve the timeliness” of death surveillance during heat waves.

A state health department spokesman said the agency is still working on those recommendations and has made progress on six of them.

When California’s worst heat wave in more than 50 years struck in 2006, killing an estimated 650 people and overwhelming hospitals, it should have been a wake-up call, said Paul English, who worked as an environmental epidemiologist for the state health agency for more than two decades and who now works for the Public Health Institute. Instead, he said, requests from within the agency for funding to monitor heat-related deaths and illnesses in real time were denied.

[CDPH is] mostly driven by the crisis of the moment. Timely information is really important, but the system to track statewide deaths and ER visits in real time has not been developed.Paul English, Tracking California

Click below to read the full story in the Los Angeles Times.

Originally published by Los Angeles Times

More Updates

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.