Update

How Has News Coverage of Gun Violence Changed Since Columbine?

-

Focus Areas

Alcohol, Tobacco, Drugs & Mental Health, Healthy Communities -

Issues

Violence Prevention -

Programs

Berkeley Media Studies Group

On April 20, 1999, Columbine students Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold opened fire in their high school in Littleton, Colorado, killing 13 people and injuring two dozen others before killing themselves. Although it wasn’t the first school shooting in the United States, the magnitude of the massacre thrust gun violence into the media spotlight in an unprecedented way and has remained a defining moment in our national memory ever since.

In the weeks and months that followed, journalists examined everything from bullying to violent video games to lax gun regulations as possible factors that contributed to the mass shooting. They wanted to know: Were there any warning signs? How did the shooters obtain their weapons? Did they have a history of violence? How can this be prevented?

News coverage offers a window into how the public and policymakers understand key issues like gun violence, and so after the Columbine shooting, PHI’s Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) set out to study coverage of similar events. Building on our previous research on violence and guns in the news, we analyzed a year’s worth of media reporting on youth violence in California and debates surrounding gun violence in the Midwest, and wrote recommendations for advocates and journalists covering these issues.

Tragically, nearly 200 school shootings have taken place in the U.S. since Columbine, and each time the public is left asking the same questions. In the aftermath of more recent tragedies like the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012 and this year’s shooting in Parkland, Florida, reporters and public health professionals have also begun to ask: Will this be the wake-up call that finally makes gun violence prevention a reality?

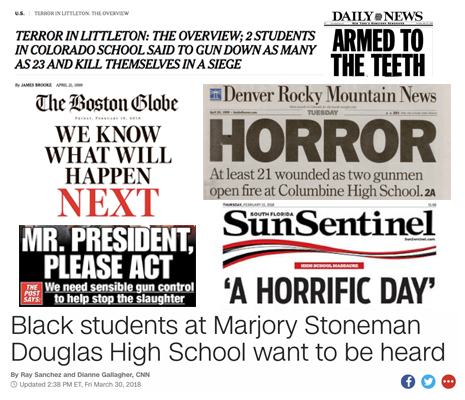

News headlines following school shootings in Littleton, Colorado, and Parkland, Florida.

As we near the 19th anniversary of the school shooting at Columbine High School, and as BMSG prepares to publish new research on news coverage of gun violence, I sat down with our head of research, Pamela Mejia, to talk about her memories of Columbine, how media coverage of gun violence has changed over the past two decades, what details are often missing from coverage, and how both journalists and advocates can help the public better understand the root causes of and solutions to gun violence. The following is an excerpt of our conversation.

Can you tell me a little bit about your memories of the Columbine shooting and how it has impacted your life?

I was 13, and I’d been taking some college classes in the afternoons and summers at Washington State University where my mom taught. There had been some discussions about what I would do the following year, but the plan was still to attend the local high school. Columbine changed all that. Suddenly the idea of me being inside a school building was very traumatizing for my mom.

I remember images and videos on the news that showed the shooters inside Columbine High School. I could see the cafeteria tables and the hallways and the library, and it was all so recognizable. Places that had been normal before were suddenly dangerous. My mother was so panicked that she didn’t want me going back to a public middle school or a high school. So the following year I enrolled in college full time. It’s a long story and there’s more to it than that, but ultimately, Columbine changed the trajectory of my academic life.

Looking back now, even though there had been shootings before Columbine, it definitely felt like a defining moment. If you started going to school after 1999, you grew up in an era where school shootings were just part of your life.

How did the Columbine shooting affect your career, and has it influenced the work you are doing as a media researcher?

Now that I’m a mother, I can understand what my own mom was going through. My work is shaped by my memories of Columbine, and reading the news, and being surrounded by gun culture in America, but it’s also shaped by my family. I’m raising a child and I’m married to a high school teacher, and I want to figure out how to make a compelling case for gun control so that my husband isn’t expected to be a human shield and so that my daughter doesn’t grow up thinking lockdown drills are a normal part of life.

In the long term, we work in public health because we want the world to be better. But with violence prevention, it feels urgent. We’re doing it so next week will be better, or so that tomorrow will be better.

What research is BMSG doing to understand how the media are covering gun violence?

In much of our research on gun violence, we are deliberately not looking at mass shootings. Mass shootings are terrible tragedies and we need to talk about them, but if you’re looking at the numbers, they actually don’t account for most of the deaths from guns. The majority of gun deaths and injuries are caused by suicide, domestic violence, and community-level violence. We’re trying to understand the gun violence that kills and injures and traumatizes people every day and how it’s covered in the media.

And there is room for improvement in news coverage. We can’t solve a problem we don’t know is happening—when you tell people that 2/3 of gun deaths are suicides, that is news to them. When you tell them that one of the best ways to stop gun violence deaths is to address domestic violence, they’re shocked. That’s just not the narrative they know. They think it’s all mass shootings because that is what they see in the media.

The trauma and suffering from gun violence that happens every day can feel swallowed up by coverage of mass shootings and school shootings. When they happen, they’re everywhere in the news, and then the coverage goes away. But every day, many more people are dying, becoming injured, or being traumatized because of the more common kinds of gun violence, and we’re not really talking about or aware of that.

Is there still value in studying news coverage of school shootings, despite their relatively rare occurrence compared to other forms of gun violence?

Yes, one of my research dreams is to take a deep dive into the coverage of every mass shooting that has happened in 20 years to see what it looks like and how it has changed over time. There’s value in looking at the incidents that drive coverage, the narratives that arise, and how we understand what it means to live in a violent society.

Looking back 19 years from the Columbine shooting, there are some key similarities in coverage of more recent shootings, but it feels like there may be an important shift happening in how the media report on school shootings. I’ve done some preliminary analyzing, but we won’t know for sure until we study it further.

What patterns are you seeing so far in how the media cover mass shootings and school shootings?

We’ve started doing research to look at school shootings since Columbine and to see how coverage ebbs and flows in the week following an event. We’ve found that there is always a spike in coverage after shooting, but it dissipates by the following week, or even sooner. Some research shows it can drop off within a week!

It seems like coverage follows an almost predictable cycle after a mass shooting: shock, grief, outrage, statements by the NRA, calls for mental health services, thoughts and prayers, decrying thoughts and prayers as not being enough—all those things happen, and then the coverage goes away.

A few stories stay in the news cycle a bit longer, like the horrific tragedies in Newtown and Las Vegas, but for the most part, coverage dies out and, as we’ve seen, gun control measures can fizzle out when the “heat” is off. I don’t have data on it, but anecdotally Parkland seems different—it’s been two months, and we’re still talking about it. I think the kids from Parkland are savvy, educated, and dedicated. They know how to talk to the media and how to use social media in a strategic and powerful way. They seem like a really amazing group, and I’m interested to see what happens next.

What else can we learn from news coverage of gun violence since Columbine?

After Columbine, reporters did a thorough job of investigating possible causes for the shooting and interviewing a wide range of sources, including youth, independent experts, and advocates. But after Columbine faded from the news cycle, coverage of gun violence no longer captured the deep context that people need to understand the problem and what to do about it. For example, BMSG’s research on media portrayals of youth and violence in California in the year Columbine occurred found that the coverage was much narrower—it included less context and quoted fewer sources. Instead of hearing from valuable voices like health professionals, we heard mostly from police and lawyers and saw the issue framed as more of just a criminal justice issue. A lot of the information that could help people see gun violence as a public health and safety issue wasn’t there.

Even today we see that pattern continuing, of journalists reporting in great depth on rare but tragic mass shootings, but taking a more surface-level approach to more common forms of gun violence. The good news is that some reporters and news outlets are starting to notice this disparity and are working to correct it. For example, I was really impressed by recent coverage from the Washington Post that highlighted perspectives from youth of color in urban areas who have grown up around gun violence but haven’t seen their experiences reported in the news.

And there are other signs of progress, too. Coverage of Parkland very quickly went from the 17 people killed to #NotOneMore—from a hashtag, to a movement, to the cover of Time magazine. It feels like it’s not just about the 17 people who were shot, and the town, and community, but also a larger conversation about gun violence in America.

Do you think that the “movement moment” that we are in, with Black Lives Matter marches and the Women’s March is helping building momentum for gun violence prevention?

It definitely seems possible. Black Lives Matter and #NeverAgain and #MeToo have forced conversations that used to be private into the media and public agendas. There are still a lot of disagreements out there. Whenever I think that people are really getting “woke,” I just check the comments section after a news article or blog, and that brings me back to reality. Still, these movements are impossible to ignore. Even if there is a lot of work to do, there is something happening. I’m especially encouraged by the connections being made by Parkland students to community violence in Chicago, or the student walkouts in Philadelphia and Miami.

Protesters gather at the March for Our Lives in San Francisco, holding signs that say “Books not Bullets,”

“Puns not Guns,”and “I shouldn’t have to die for my education.”

Photo courtesy of Katherine Schaff.

What should people know about violence prevention?

People need to know that violence prevention is happening—and that it’s possible. The news can help people see that. But, unfortunately, we have a false narrative in our society that violence is inevitable—that it is a fact of life, and all we can do is prepare to punish people after the fact by building more jails and hiring more cops.

But when people find out that violence prevention interventions like Advance Peace in Richmond have been associated with a 70 percent decline in shootings, at first, they are incredulous. But then they are inspired and motivated, and they want to know how they can be a part of it. Hearing that prevention is working changes the way people see the world they live in.

I want people to know that there are smart, committed, dedicated people out there who are doing the work to prevent violence when and where it happens—that they need support, funding, and feet on the ground. And they’re only going to know that if those stories are making headlines, you know?

I am a drag at cocktail parties because I will not stop talking about why we need to change the narrative to show that we don’t have to accept violence as just part of our world and our society. If we engage with prevention to the extent that we engage with violence, then we will be able to accomplish significant change and better people’s lives. That’s what I want people to know. It’s possible. It’s happening, and it belongs to all of us. It’s our privilege and our responsibility and our right. But if that narrative isn’t included in our primary way of having a broad public conversation—news coverage—then people won’t know about it.

What can advocates do to illuminate the root causes of gun violence?

In public health, we know that what surrounds us shapes us, so there can be the temptation to say, “the root cause gun violence is racism, sexism, or capitalism, or oppression”—that is all true. But it’s impossible to help people see that in a 20-second sound bite. So, you have to start small and then make a connection between an isolated event and the bigger picture.

To use some recent examples in Parkland, the students have done a good job connecting the act of violence to bigger issues surrounding gun control. Yes, this is about a troubled person who did a terrible thing. But asking, “Why did he have the access to the weapon that took him from being a troubled kid to a mass murderer?” has helped people make the leap from a bad guy with a gun to a need for gun violence prevention policies. If you can help people take that one step back, you’ve opened a door to a conversation where you actually might be able to get to those big-picture issues, to talk about systems and policy change and oppression and capitalism—about the racism that causes Black children to have the highest rates of firearm mortality overall, and the patriarchy that leaves guns in the hands of convicted domestic abusers. But you’ve got to start somewhere.

What can reporters do when covering chronic gun violence?

Journalists have professional commitments and conventions and time crunches. Their job is harder now than ever, and I want to say, many of them do a really great job. We’ll be publishing our official recommendations for reporting on gun violence and suicide, domestic violence, and community violence in June, but right now I would say:

- Find sources that represent different community perspectives

We’ve seen that police, district attorneys, and others from the criminal justice system dominate news coverage. They have an important perspective, but it’s not the only one. When identifying sources for reactions, reporters could look for people outside of the criminal justice system, such as prevention advocates or faith-based leaders, who can give a perspective on how violence is impacting their community. - Keep up existing standards of reporting that are working well

There are already journalistic conventions surrounding suicide coverage meant to decrease the risk of copycats, and those are working well. Adhering to those standards—and applying similar standards to other forms of gun violence, like domestic violence—is a great idea. - Be intentional about images tied to your gun violence reporting

Especially in stories about domestic violence, we found that the images associated with the stories overrepresent people of color. This is also true for community violence. If the only thing you knew about these types of violence was what you got from the media, you would think that this is a problem that primarily affects communities of color. That’s not true, and it’s dangerous and unfair to have a public narrative that implies that’s the case.

Do you think media coverage of gun violence has changed since Columbine? Have you seen media coverage that helps illustrate root causes of gun violence? Share your thoughts with BMSG on Twitter, Facebook, or by email. Be sure to stay tuned for our upcoming report on news portrayals of community violence in June.

Originally published by Berkeley Media Studies Group

More Updates

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.