Update

Meeting People Where They Are: Delivering Culturally Congruent Health Messages

- Whitney Hall, Administration & Communications Specialist

-

Focus Areas

Capacity Building & Leadership, Global Health -

Issues

Workforce Development -

Programs

PHI/CDC Global Health Fellowship Program

Take the word mosquito and replace it with sancudo (the word most often used in place of mosquito across Central America) in a public health infographic, and you have just strengthened your message about the prevention of mosquito-borne illnesses across the region, Jahn explains. Jahn Jaramillo, MPH, is a 3rd year PHI/CDC Global Health Surveillance Fellow for the Division of Global Health Protection within CDC’s Central America Regional office in Guatemala. Not only language, he points out, but how a message is communicated and by whom, is crucial to implementing effective messages to create healthy choices, and even save lives.

Not only language, he points out, but how a message is communicated and by whom, is crucial to implementing effective messages to create healthy choices, and even save lives.

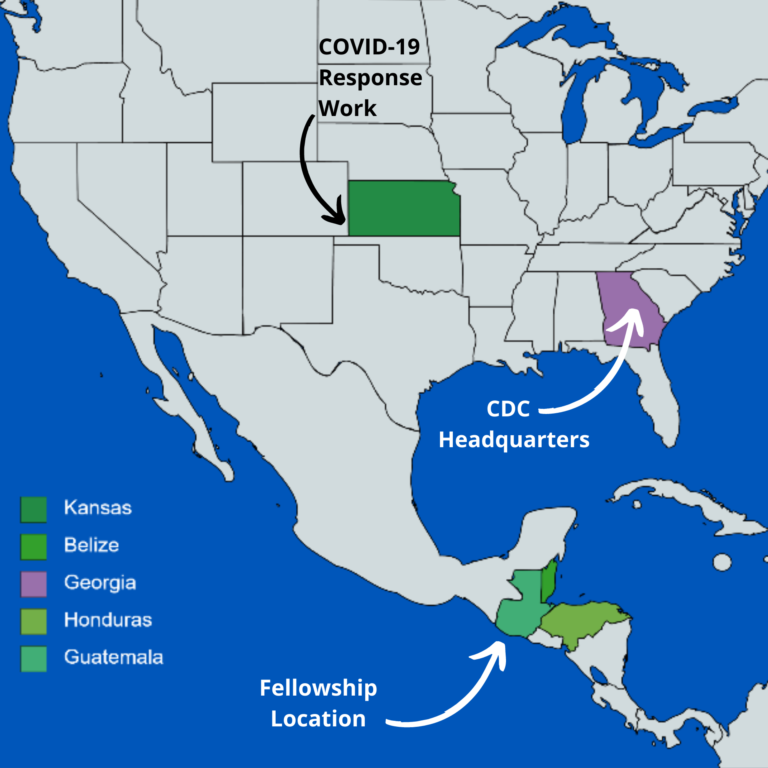

Bilingual in Spanish with a background in global health research, HIV, and tuberculosis (mainly in the US, Thailand, and the Philippines), Jahn has spent the past 2 years working in Guatemala with CDC. Since June of this year, he has been temporarily based in Atlanta, home of CDC Headquarters, supporting the Guatemala office remotely and working on CDC’s COVID-19 response in the U.S. in Latino immigrant and refugee populations. Both his experiences in the US and in Central America with CDC have reinforced and heightened his awareness of the importance of multi-cultural and multi-lingual messaging.

With CDC’s Emergency Operations Center, Jahn worked under the Global Migration Task Force, Mobile Populations Team to support the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Jahn interviewed community leaders and employees of meatpacking plants in Southwest Kansas to address COVID-19 spreading among workers at the plants. Given that employees are largely immigrants or refugees, Jahn quickly realized that to prevent outbreaks in these communities, there are language needs not only in Spanish, but also in Mayan dialects, Arabic, Haitian Creole, and Burmese, among others. Often, it is what is not being said that signals a disconnect. This is especially apparent when interviewees respond with brief or one-word answers to questions regarding behaviors and attitudes about health, implying that they may not be able to understand the posted health mandates or information in English. While technology has increased the ease of speaking with participants in other states, not having face to face interaction makes it harder to build trust especially in vulnerable or marginalized populations where there is apprehension about outsiders who they may not trust, particularly government agencies that they might not have a connection with. These challenges emphasize the importance of using a participant’s native language in interviews to better understand health communication needs amidst a pandemic. Jahn recognized that “culturally congruent messaging” is a key priority to guide workers to healthy decisions and prevent COVID-19 from spreading. His team found that informal community leaders with a higher proficiency of English amongst their peers often are the ones who communicate messages to their respective communities. As such, these leaders serve as a bridge that unites their community with important public health information, so it is especially crucial to include these leaders in future plans to increase engagement/participation within studies and strengthen prevention tactics.

Jahn recognized that “culturally congruent messaging” is a key priority to guide workers to healthy decisions and prevent COVID-19 from spreading.

Similarly, in Central America, Jahn has helped create and strengthen health communications for CDC’s Central America Regional office (CAR). In Honduras, Jahn was part of the dengue outbreak response alongside CDC epidemiologists, clinicians, and laboratory specialists. In Honduras, CDC has printed thousands of health communications materials for local clinics and hospitals to educate communities about dengue. Working across the region, it is important to deliver effective messages and help make CDC’s work visible, both to understand diseases better, and justify the need for continued funding of vital public health projects.

This work comes at a historic time aside from the pandemic- it is the first time in history that several countries in Central America, including Belize, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, have collaborated with CDC to monitor and quantify the occurrence of acute febrile illnesses (AFIs). Various US universities currently partner with CDC CAR to conduct surveillance work on AFIs to help assess why someone has a fever and ultimately what the burden of disease is in country. As a Fellow, Jahn met with the Honduran Minister of Health, Alba Consuelo Flores, earlier this year on behalf of a CDC-funded research initiative with Harvard and Yale University to expand AFI surveillance to Honduras and respond to a recent dengue outbreak. The Minister enthusiastically agreed to this partnership and Jahn covered his response to the dengue outbreak on CDC’s Center for Global Health website. Additionally, he met with the Director of Communications at the Ministry of Health, which was an “eye opening and amazing opportunity” to help develop fact sheets about dengue and prevention, and provide resources CDC has internally while working with the local government to contextualize their messages under a local context. This opportunity helped the Honduran government understand what CDC can offer, and the exchange of ideas was a lesson in what the US can learn from Honduras’ successes in public health, while furthering diplomatic relationships between the two countries.

Strong communications, along with investment in global health diplomacy and engagement with public health leaders across countries, can help improve the understanding of a population’s health needs. Collaborative partnership across agencies including the US Embassy, USAID, CDC, and Ministries of Health are key in advancing the health of populations in Central America, fostering strong diplomatic relationships and furthering CDC/US interests while help saving lives. As a global health professional, Jahn considers how CDC can best convey important health information to the public, and carry out best practices. In Guatemala, he has seen this via interpersonal interactions with comadronas– women who have built trust in their communities as a health information resource and play a similar role to a mid-wife. In more rural areas of Guatemala, information has traditionally been spread orally, and what works in one community might not work in another. Messages take on anthropological lives of their own and must be adapted to community preferences and needs.

Strong communications, along with investment in global health diplomacy and engagement with public health leaders across countries, can help improve the understanding of a population’s health needs.

Now, CDC CAR is incorporating COVID-19 into AFI surveillance, by figuring out how to use this existing regional platform to help ministries of health and participating Central American countries determine the burden of COVID-19. As Jahn heads back to Guatemala this fall, he hopes to take the lessons he has learned from the COVID-19 response in the US to ask the right questions from the people he is addressing, before he can help circulate the right answers. Whether through site visits or monthly calls with partners, it is important, he says, to “help clinicians and providers make decisions to save lives and promote the wellbeing of different populations.”

Read more about CDC’s work in Central America here.

Originally published by PHI/CDC Global Health Fellowship Program

More Updates

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.