In the News

Punjabi Sikh Truckers Lack Access To COVID-19 Information

- NPR Science Friday

-

Focus Areas

Communicable Disease Prevention, Healthy Communities -

Issues

Rural Health -

Programs

Together Toward Health -

Strategic Initiatives

COVID-19

The cab of Sunny Grewal’s 18-wheeler is neat and tidy. He’s got bunk beds with red checkered sheets and gray interior cabinets that hide a fridge, microwave, paper plates and spices for long days on the road. One plastic container holds bite-sized sweets from his native India. “We call it gur, G-U-R,” Grewal says. “You can put it in tea, or you can have a small piece after food.”

Grewal is a trucking company owner-operator based in Fresno. He’s on the road upwards of 150,000 miles a year, delivering produce and cleaning supplies like hand sanitizer to and from the East Coast, the Midwest, and the South. In other words, his work is essential to keeping this country running. “If nurses want to take care of you, they need the stuff that we bring,” he says. “You want to buy food to stay home, you’re going to stock the food in your house, we bring that food.”

Early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, the state of California designated truckers as essential workers, but that status hasn’t materialized into any tangible advantages or privileges.

Singh and Grewal are also among an estimated hundreds of thousands of truckers in the U.S. who are Sikh, from the northern Indian state of Punjab. The North American Punjabi Trucking Association estimates Punjabi Sikhs make up 20 percent of the country’s truckers and control as much as 40 percent of the industry in California, and yet few public health departments in the state offer critical COVID-related information in the Punjabi language. “It makes me feel left over, you know?” says Grewal.

That lack of information has had consequences for the whole Punjabi-speaking community, says Manpreet Kaur of the non-profit Jakara Movement, especially in the early days of the pandemic. “The information was just always missing or it was too late or it was shared in a way that wasn’t easily understood,” she says.

Kaur recalls a day last year she was standing outside a Sikh temple known as a Gurdwara in Bakersfield, when a woman standing near her asked her to stop practicing social distancing and move forward in line. “She was like ‘no, that’s not how the virus is passed, it’s through surfaces,’ and I’m like that is at least six-month-old information,” Kaur says.

It’s difficult to quantify the stakes of the pandemic for California’s Punjabi Sikh population, but many cities with large diaspora, like Livingston and Yuba City, have case rates that far exceed their county averages. The Jakara Movement estimates that at least four Punjabi Sikh workers were among the 14 who died in COVID outbreaks at Foster Farms poultry processing plants in Merced and Fresno Counties. “Punjabis tend to be in food processing, trucking, all of the essential work that has high exposure,” Kaur says.

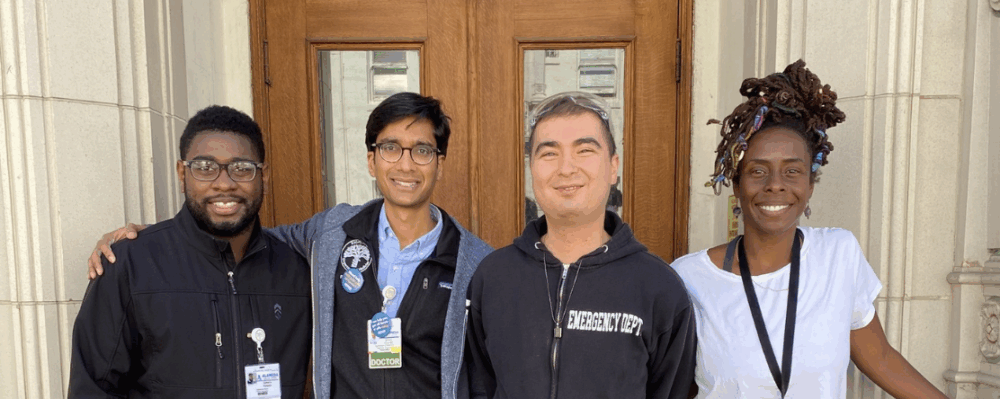

So, early on, the Jakara Movement, an organization that fosters leadership and community-building among Punjabi Sikhs and other underserved communities, began translating important health information into Punjabi. They created culturally sensitive visuals, like a graphic of a Punjabi grandmother getting her COVID vaccine, and a video about vaccinations featuring Punjabi Sikh doctors.

Jaspreet Singha, another truck owner-operator based in Fresno, says there’s an intimacy in receiving information in his native tongue, even though he’s proficient in English. “It makes you feel more recognized, makes you feel, yes, your hard work is paying off when your country needed you,” he says.

Click below to read the full story from NPR Science Friday.

Originally published by NPR Science Friday

More Updates

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.