In the News

The Atlantic: PHI Experts Discuss the Impact of Air Pollution on Communities in Southern California’s Industrial-Port Belt

- The Atlantic

“Jo Franco still remembers the moment she realized that her nose worked. Growing up in Wilmington, a Los Angeles neighborhood dotted with oil refineries and next to one of the largest port complexes in the country, she’d always assumed she had a fever, or allergies: “I could never breathe through my nose at all,” she told me. But when she moved away from the city for college, her breathing suddenly got easier. “It was this wonderful surprise,” she said. “I could smell lemons.”

Franco can still map Wilmington’s refineries, and still remembers the chemicals they’d release into the sky. At 28, after moving back to California, she was diagnosed with cervical cancer. When she was in her 30s, former high-school classmates started dying. Then Franco developed another cancer: acinic cell carcinoma, a rare cancer of the salivary glands. Doctors sliced open the skin on the right side of her face to remove a tumor the size of a golf ball. Two years later, the tumor came back, and Franco underwent aggressive radiation treatment that made her feel like she got “punched in the jaw.” She was in her mid-50s.

In 2020, after a childhood spent in Los Angeles County and several adult years in Long Beach, I embarked on documenting what longtime residents like Franco had been experiencing for generations in this industrial-port belt. I dodged 18-wheelers in between errands, saw fine dust lingering in the air, and biked along the trash-clogged Los Angeles River. I could see smokestacks pummeling the sky. Even inside, I could sometimes smell the rotten-egg odor from the oil wells, where tens of thousands of barrels of crude were produced every day, to be shipped around the world.

More than 300,000 people live in communities near the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the first- and second-busiest in the country, and their neighborhoods are defined by the machinery of Big Industry. The I-710 routes thousands of diesel trucks through low-income areas; in 2023 alone, those trucks transported 8.6 million containers. The Wilmington Oil Field is the third-largest in the contiguous United States, and the seven refineries in Los Angeles County can produce 1 million barrels a day total, 60 percent of California’s total oil-refining capacity. Recently, a warehouse and logistics boom throughout Southern California has transformed residential streets into commercial roads.

Around the start of the pandemic, Jose Ulloa, a 27-year Wilmington resident, saw his street turned into a truck route. Parts of the neighborhood were quickly covered in thick layers of dirt, he told me, while dust and fumes hung in the air as trucks roared down the street. Some residents began to complain about their respiratory health. Ulloa was diagnosed with acute bronchitis, which eventually developed into a severe case of asthma that lingers today.

“Sometimes this cough won’t let me sleep, or my family,” Ulloa said, between wheezes. “And before, the cough was so bad, it would hurt my stomach [and] my back, almost like you were doing exercise.” Our interview was cut short because he had a minor asthma attack. I watched him fumble to his bedroom and grab his inhaler for relief. “This has completely changed his life forever,” said his wife, Imelda, shaking her head from the living room.

Bad air is invisibly violent. Nitrogen dioxide and chemically coated particulate matter—the by-products of industrial activity—have been repeatedly linked to cancer, decreased lung function, and chronic respiratory diseases. Children who are exposed to toxic air and develop asthma may have trouble breathing for the rest of their life, Joel Ervice, the associate director of Regional Asthma Management and Prevention, told me. Paul English, who recently retired from his job as a researcher and director for the Public Health Institute, told me studies have shown that particulate matter is especially concentrated in low-income neighborhoods.”

Click on the link below to read the full article. Registration or subscription may be required to access this full story.

Originally published by The Atlantic

More Updates

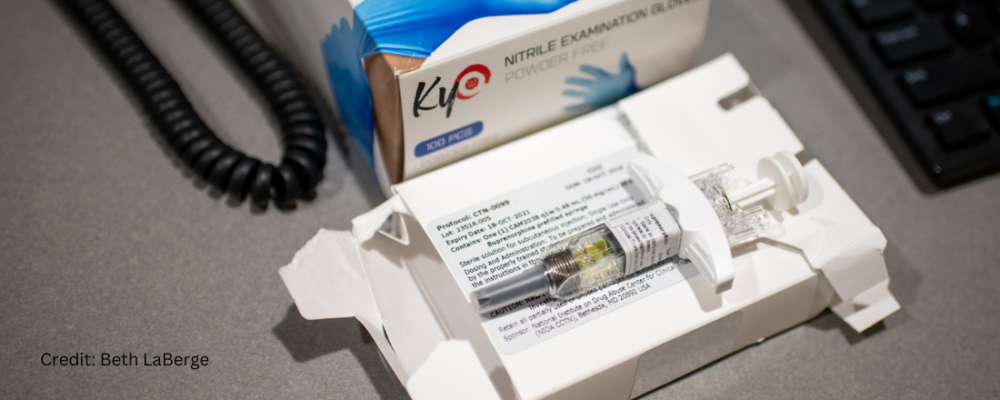

New Study Shows Emergency Physician Prescribed Buprenorphine Effectively Helps Patients Struggling with Opioid Addiction get Started on Path to Long-Term Recovery

PHIL Collective: Tools, Training and Resources for Collaborative, Cross-Sector Efforts to Improve Health and Equity

NY Times Magazine Features PHI’s Bridge Center on Buprenorphine as an Effective Treatment for Opioid Addiction

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.