In the News

The Surprising Connection Between West Coast Fires And The Volatile Chemicals Tainting America’s Drinking Water

- Ensia

-

Focus Areas

Environmental Health -

Issues

Wildfires & Extreme Heat -

Expertise

Research – Quantitative

From his back deck, Bogdan Marian can see the scars running down into the San Lorenzo Valley: the pad of a destroyed home, the scorched brown trees at the ridge line.

Marian is grateful to have a standing home. Yet his family and many others in the area still face another worry: the safety of their tap water. After fires marred the valley near Santa Cruz, California, in August, the local water district issued a “Do Not Drink Do Not Boil” notice to residents.

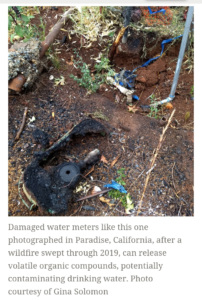

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) including benzene, residents were warned, could be seeping into the water system — just as the toxic chemicals did in Santa Rosa and Paradise, California, in the wake of wildfires in 2017 and 2018.

VOCs are a large group of chemicals that share an ability to vaporize in air and dissolve in water. Since the 1940s, they have been widely used in industry, agriculture and homes. They are components of gasoline, glues, degreasers, dry cleaning fluids, pesticides plastics and more. In addition to the notorious threat they pose to indoor air quality — off-gassing is common from new cabinets or laminate flooring, for example — VOCs can also find their way into the environment, tainting soil and water.

While VOCs that migrate into surface waters tend to evaporate, VOCs that travel through the soil and into groundwater can stick around and, ultimately, contaminate drinking water supplies. However VOCs get into drinking water, it can be bad news.

If you’re talking about something like lead in the water, you want to avoid drinking it. If you’re talking about VOCs, then you really don’t want to get those on your skin. Even a dishwasher creates vapor that could be inhaled,Dr. Gina Solomon

Former director of PHI’s Achieving Resilient Communities (ARC) and PHI’s Science for Toxic Exposure Prevention

Research has linked exposure to VOCs with increased risks of health effects including anemia, leukemia, kidney cancer, reproductive problems, birth defects and nervous system damage.

In general, children are at greatest risk from exposure to VOCs, explains Solomon. They take in a greater amount of fluid proportional to their body weight, compared with adults. And they have a lot more relative skin surface for their small size, resulting in a higher dose if bathed in the water.

“Benzene is also notorious for delayed health effects,” says Solomon. “The younger you are the more likely you are to live long enough to encounter those health effects.”

Wildfire Connection

Wildfires as a source of VOCs in drinking water had not really been on the radar until the Tubbs Fire burned through large swaths of Santa Rosa, California, in 2017. After the blaze, drinking water samples from municipal supplies had levels of several VOCs, including benzene, above state and federal exposure limits.

Wildfires as a source of VOCs in drinking water had not really been on the radar until the Tubbs Fire burned through large swaths of Santa Rosa, California, in 2017. After the blaze, drinking water samples from municipal supplies had levels of several VOCs, including benzene, above state and federal exposure limits.

The next year, the Camp Fire devastated the town of Paradise, California. Benzene and other VOCs popped up in drinking water tests there, too.

Solomon notes that benzene is known to cause cancer in humans. “It’s an alarming thing to find,” she says. And benzene was just one of several VOCs detected in various water samples collected after the fire.

Regulatory Lessons

The EPA regulates 21 VOCs under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Community water systems are required to monitor for these chemicals and, if their tests detect levels greater than the maximum contaminant level set by the EPA, they must inform their customers of the violation and take steps to remedy the situation. Still, Solomon suggests the EPA’s regulations may not go far enough to protect the public from VOC contamination.

Methylene chloride, a VOC that appeared at levels above EPA limits in both Santa Rosa and Paradise, illustrates one potential reason. Federal and global health agencies consider it a probable human carcinogen. But standard drinking water testing might very well miss it. That’s because EPA requires that water systems test at the tap for lead and copper, but other tests for contaminants are done at the water treatment plant, explains Solomon. She notes a hypothesis that methylene chloride can form from a reaction among water pipes, disinfection byproducts and chlorine — contaminating water after it leaves the plant.

Cleaning Up

Increases in testing, largely resulting from recent awareness of their potential presence after wildires, along with improved treatment technologies in recent years means VOCs are less likely to reach the tap. Among the popular treatment tools are activated carbon filters that can absorb the chemicals and a process called air stripping, which can remove or “strip” benzene and other VOCs by contacting clean air with the contaminated water. The air movement causes the chemicals to evaporate at a faster rate. Such a system was installed to clean up industrial contaminants in California’s San Fernando Valley. Luthy notes that air stripping is the go-to method for cleaning up groundwater polluted by gasoline stations.

That said, both testing and effective treatment technologies come at a cost. “As soon as we start talking about private wells and small water systems, all bets are off,” says Solomon, referring to the tight budgets and limited staff generally available in these situations to invest in testing and treatment. “The dollar signs start piling up when you start testing that well. And in order to ensure your well is safe you really have to test periodically. If there are no contaminants today, that doesn’t necessarily mean there will be no contaminants a year from now.”

She notes that many homeowners and very small water systems simply skip the testing, especially with limited regulations holding them to do it.

A lot of homes so far affected by 2020 wildfires have been in areas with private wells or small to very small systems. “Those systems are getting some help from the state,” says Solomon, noting that residents in Paradise and surrounding areas also benefited from an emergency federal grant for free testing. “But that’s not typical.”

The “Do Not Drink Do Not Boil” notice has now been lifted for Marian’s neighborhood. But Marian remains cautious until more tests are done. “I’m comfortable enough to use tap water for laundry and cleaning the house,” he says. “But out of an abundance of caution, we’re still using bottled water for drinking and cooking.”

Click below to read the full article in Ensia.

Originally published by Ensia

More Updates

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.