In the News

Why Warning Pregnant Women Not to Drink Can Backfire

-

Focus Areas

Alcohol, Tobacco, Drugs & Mental Health, Women, Youth & Children -

Issues

Alcohol -

Programs

Alcohol Research Group

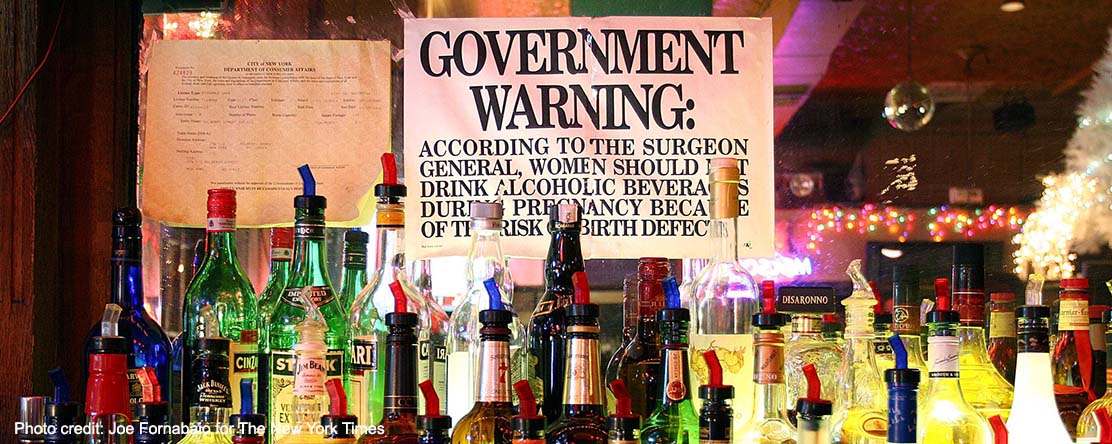

Photo by Joe Fornabaio for The New York Times Photo by Joe Fornabaio for The New York Times |

In many areas of health policy, the best of intentions can lead to more harm than good. Such is the case with America’s approach to alcohol and pregnancy.

The best evidence shows that punitive policies—such as equating drinking while pregnant as child abuse and threatening to involve child protective services—can dissuade women from getting prenatal care.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders refer to a collection of problems in babies and children. These include low birth weight; impaired growth; and problems in the heart, kidneys and brain. Children can have developmental delays, communication difficulties, learning disabilities and lower I.Q. Some of these last a lifetime.

It’s hard to know how many American children are affected.Studies done by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have estimated that between 2 and 15 infants per 10,000 born in the United States have fetal alcohol syndrome, the most severe form of the disorders.

Some community-based studies that use the broader definition ofthe disorder have found more affected children, up to 5 percent.

We know that infants of women who drink alcohol in pregnancy may develop these disorders. The problem is what we don’t know. We don’t know the level of alcohol exposure in utero that could cause a child to develop these disorders. We don’t know if the timing of the exposure matters. We don’t know why some women who drink little might have a child who is affected, while some can binge drink during pregnancy and have a child with no apparent problems.

Because of this, most medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the C.D.C., recommend that women forgo alcohol during pregnancy. The only dose known to be “safe” is none, they say, and therefore women should not drink at all.

Many women in the United States comply with this directive. But a significant number do not.

A study published in April found that 11.5 percent of women who are pregnant report drinking alcohol. Almost 4 percent report binge drinking — defined as four or more drinks on any occasion — in the last month. Given that women may be ashamed to acknowledge this, the true numbers may be higher.

To combat this, 43 states have enacted policies. These can be affirmative measures, like giving pregnant women priority for substance-abuse treatment, or punitive ones, like defining drinking alcohol during pregnancy as child abuse or neglect.

Proponents of such policies believe that they are making things better, especially for children. A recent study suggests they’re wrong.

Researchers gathered birth certificate data for more than 155 million live births from 1972 to 2015. The researchers were interested in how many children were born at a low birth weight or prematurely. They compared the rates of these undesirable outcomes in times and places when alcohol-pregnancy policies did and did not exist. They controlled for a number of demographic and related factors, including those known to be associated with poorer birth outcomes, like poverty and cigarette smoking.

They found that policies that defined alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse or neglect were associated with an increase of more than 12,000 preterm births. The cost of these were more than $580 million in the first year of life. Policies mandating warning signs where alcohol was sold were associated with an increase of more than 7,000 babies born at low birth weight, at a cost of more than $150 million.

A previous study looking at how these policies affected women’s drinking found mixed results. States with punitive policies had more drinking, not less. Over all, neither type of policy seemed to be associated with lower levels of drinking.

It’s possible that states that already had more drinking might have put such policies in place in response to it. But the research methods used accounted for this and state-level data on drinking, and the prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders weren’t available when most of the policies were enacted, making it hard to believe that the relative levels of problems were what spurred policymakers to act.

Originally published by The New York Times

More Updates

Safeguarding the Health and Wellbeing of Agricultural Workers in Monterey County: A 5-Year Glance at the COVID Pandemic & Lessons Learned

New Study Reveals Why Alcohol Use Increased During the Pandemic

PHIL Collective: Tools, Training and Resources for Collaborative, Cross-Sector Efforts to Improve Health and Equity

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.