Policy Memo: Advancing Racial Equity in California State Government

- Hye Sun Kim, MPP

-

Focus Areas

Healthy Communities -

Issues

Health in All Policies -

Expertise

Public Policy Development -

Programs

State of Equity

Advancing Racial Equity in California State Government: A strategic analysis of recommendations to institutionalize racial equity in California state government

Executive Summary

The author recommends:

- Establish a statewide Office of Equity.

- Expand and adjust the Capitol Collaborative on Race & Equity (CCORE) to build groundwork for an Office of Equity.

Structural racism persists in U.S. society to this day. The current coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is highlighting and exacerbating racial inequities, with millions of people of color experiencing disproportionate impacts and increasing vulnerabilities due to racial inequities. Historically, governments have created, maintained, and exacerbated these inequities – including California state government.

The mission of California state government is to serve all Californians, and Gov. Gavin Newsom’s “California for All” message clearly vocalizes this. To serve all Californians, the state government must advance racial equity and center the needs and desires of communities of color, especially those that have been marginalized and oppressed. Just as racism is a structural and intersectional issue, racial equity must also be approached in a structural and intersectional way. Communities of color know their experiences, struggles, and solutions the best; they must be at the heart of the pursuits to achieve racial equity. Therefore, California state government must change its systems to structuralize and embed racial equity by centering on the lived experiences of communities of color in all its programs and policies.

State government has made progress in advancing racial equity through the Capitol Collaborative on Race and Equity (CCORE). The first state government-level initiative of its scale, CCORE (formerly the Government Alliance on Race and Equity Capitol Cohort) is a movement and learning community of California state government entities working together since 2018, to plan for and implement activities that embed racial equity approaches into institutional culture, policies, and practices. The initiative features a public-private partnership between the Public Health Institute and the state government’s Health in All Policies Task Force, convened in partnership with the California Strategic Growth Council and the California Department of Public Health. In addition to the community of practice, CCORE offers two capacity building components: 1) a training program for state government entities, and 2) a staff team that provides targeted coaching and peer-to-peer support to the CCORE community.

For this report, the author conducted 26 interviews to understand and compare the following three strategy alternatives according to impact and feasibility: 1) continue CCORE, as-is; 2) expand and adjust CCORE; and 3) establish a statewide Office of Equity. This report lists necessary factors and considerations for creating the proposed Office of Equity, along with common themes identified from the interviews.

Based on the findings, the author recommends that CCORE be expanded and adjusted in the immediate present to build momentum for establishing a statewide Office of Equity, which will structuralize and embed racial equity across the state government. The Office of Equity will result in high impact and necessary coordination of racial equity work and community engagement across the state government. These actions are imperative especially as the COVID-19 crisis demonstrates that racial equity cannot be optional but must be a priority for California state government.

Part I: Problem Definition, Methods, and Background

Problem Definition

Throughout the history of the United States, government at all levels has played and continues to play a significant role in creating, maintaining, and exacerbating racial inequities through policies, systems, and practices. California is no exception. Despite significant efforts over the course of recent decades to ban discriminatory action and remedy harms, communities of color continue to be especially harmed by racial inequities, which contradict the government’s mission to serve all its people. State government will need to radically transform its systems to achieve racial equity for all Californians.

This report responds to the problem definition by providing recommendations for system changes to normalize, organize, and operationalize racial equity in California state government.

Methods

The author conducted this research following the policy analysis protocols of the Goldman School of Public Policy. This involves use of the “Eight Fold Path” developed by Eugene Bardach:[i]

- Define the problem

- Assemble the evidence

- Construct the alternatives

- Select the criteria

- Project the outcomes

- Confront the trade-offs

- Decide

- Tell your story

Additionally, the author reviewed documents for establishing background knowledge on the report, including prior analyses of surveys on the Capitol Collaborative on Race and Equity (CCORE) participants, Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) documents, Washington state’s Office of Equity Preliminary Recommendations, etc. The author also applied the GARE framework of “normalize, organize, operationalize” to the themes found from interviews.

Interviews

The author conducted 23 phone interviews with 26 informants between late February and late April of 2020. Informants consist of employees and leaders within California state government, including participants in CCORE; employees from other state governments; and subject matter experts. Three interviewees requested anonymity. Interviews ranged from 30 to 60 minutes. The author conducted most interviews based on recommendations from the Health in All Policies (HiAP) Task Force staff and the remaining interviews using snowball sampling.

All quotes and information, including those that are anonymized or not attributed, were confirmed with each informant when possible.

Background

California State Government’s History of Structural Racism and Commitment to Social Justice

To envision a future that achieves racial equity, California state government must understand its past and present. The state government faces a long history of structural racism and bigotry. Though California banned slavery when it was first established as a state in 1850, the first state governor banned Black people from moving to or living in California, which had already started in the 1840s and continued in the 1850s.[ii] Between the 1840s and 1870s, the state government declared a “war of extermination” against Indigenous populations, known as the California Genocide.[iii] The state enacted Jim Crow laws that remained in effect through the 20th century to reinforce racial segregation against Black, Asian, Latine, and Indigenous populations.[iv] California participated in the mass deportations of 2 million residents of Mexican heritage in the 1930s and 1940s.[v]

Beginning in the 1930s, redlining and housing discrimination against people of color led to further segregation and gentrification that exist to this day. These practices prevented people of color from building wealth while facilitating ongoing mass investments almost exclusively to White people.[vi] Mass incarcerations in California has further systematized the disenfranchisement of Californians of color. Two examples, among many others, are the Japanese internment camps of the 1940s[vii] and the three strikes legislation that disproportionately punished Black men in the 1990s.[viii] Dog whistle politics also created resentment, fear, and blame against people of color, leading to disinvestments to communities of color and an increase in policing and mass incarcerations.[ix] The list goes on, and Californians of color live with the persistent effects of these injustices.[x]

California state government continues to play a role in structural, systemic racial inequities. In addition to creating racial inequities, the state government has maintained and even exacerbated them over time. Racial inequities prevent the state government from fulfilling its mission to serve all Californians, especially when state government directly contributes to the racial inequities itself.

“If in fact you’re trying to make sure that all people are benefiting, succeeding, and participating fully in the economy and society [but] you have ongoing racial inequities that are marginalizing specific groups of people from doing that, then you can’t be an effective government entity.”

– Dwayne Marsh, former Co-Director of GARE

To truly serve all Californians, California government has an imperative to advance racial equity. To do so, the state government needs a clear, unified definition of racial equity. However, at present, that does not exist. This alludes to the lack of a shared understanding of racial equity within the state government. For the purposes of this report, the definition of racial equity used will be a combination of the definitions from the HiAP Task Force and from PolicyLink, a national research and action institute advancing racial and economic equity. HiAP defines racial equity “when race can no longer be used to predict life outcomes and outcomes for all groups are improved.”[xi] PolicyLink defines racial equity as the “just and fair inclusion into a society in which all people can participate, prosper, and reach their full potential”[xii] regardless of race and ethnicity.

Under the current administration of California Governor Gavin Newsom, there are opportunities for significant policy change for racial equity. One example is the governor’s Executive Order that issues an apology to Native Americans for the state government’s “violence, exploitation, dispossession and the attempted destruction of tribal communities” throughout history. The Executive Order also established a tribally-led Truth and Healing Council to correct the historical record.[xiii] The most prominent opportunity is Governor Newsom’s “California for All” mission, in which he proposed a 2019-20 budget that “funds a comprehensive early childhood plan, more affordable paths for higher education, brings the state closer toward health care for all, and takes meaningful steps to addressing the housing crisis.”[xiv]

Governor Newsom’s June 1, 2020 update on racial justice demonstrations across the state are particularly relevant and serve as a call to action:

“We don’t systemically, foundationally address the root of these issues – we prune. We don’t tear out the institutional racism from all of our institutions large and small. We don’t. We know that. The community knows that. You’re seeing that manifested out in the streets. The last five days. They know that. The question is do we?”

“The Black community is not responsible for what’s happening in this country right now. We are…. Our institutions are responsible. We are accountable to this moment… We have a unique responsibility to the Black community in this country and we’ve been paying lip service to that for generations.”

“Are we prepared to do something differently about that?… What are we going to do differently – fundamentally, foundationally – not in the short run, but in the long run to do justice to this moment?”

– California Governor Gavin Newsom

The HiAP Task Force and CCORE

Established through the Executive Order S-04-10 in 2010, the HiAP Task Force strives to advance health, equity, and environmental sustainability in California. The first state-level Health in All Policies initiative in the country, the Task Force convenes 22 members of state government departments and agencies to integrate health and equity into state-level programs and policies. Task Force members include the Office of the Attorney General and the Environmental Protection Agency. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH), Strategic Growth Council, and the Public Health Institute (PHI; an independent nonprofit committed to health equity) staff the program.[xv]

One of the most notable achievements of the HiAP Task Force is the Capitol Collaborative on Race and Equity. In collaboration with the national network Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) and the HiAP Task Force, PHI piloted CCORE (then called the GARE Capitol Cohort) in 2018. The first state government-level initiative of its scale in the country, CCORE is a movement and learning community of California state government entities working together since 2018, to plan for and implement activities that embed racial equity approaches into institutional culture, policies, and practices. The initiative features a public-private partnership between the Public Health Institute and state government’s Health in All Policies Task Force, convened by the California Strategic Growth Council and the California Department of Public Health. In addition to the community of practice, CCORE offers two capacity building components: 1) a training program for state government entities, and 2) a staff team that provides targeted coaching and peer-to-peer support to the CCORE community. CCORE also facilitates enterprise-wide connections to ensure racial equity advances horizontally as well as vertically. Across 2018 and 2019, over 200 staff from more than 20 state departments and agencies voluntarily participated in the program. Below are the current participants:[xvi]

- California Arts Council

- California Coastal Commission

- California Department of Public Health

- California Department of Housing and Community Development

- California Department of Transportation

- California Department of Education

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

- California State Lands Commission

- California Strategic Growth Council

- California Department of Community Services and Development

- California Environmental Protection Agency, including:

- Air Resources Board

- Department of Pesticide Regulation

- CalRecycle

- Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

- State Water Resources Control Board

- Department of Toxic Substances Control

CCORE will launch a new Introductory Learning Cohort in August 2020 and expects at least 12 additional departments and agencies to participate including the California Public Utilities Commission, Department of Food and Agriculture, and Department of Fire and Forestry.

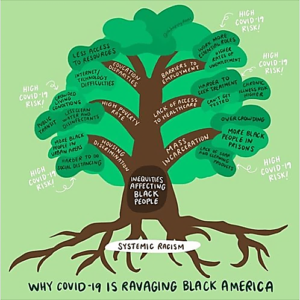

The Intersection of COVID-19 and Structural Racism

The global coronavirus pandemic is ongoing at the time of this report – and is closely related to the topic at hand. People of color are disproportionately impacted by the coronavirus across the nation, especially those who have pre-existing health conditions.[xvii] In California specifically, Black and Latine Californians are dying at a higher rate from the virus than their counterparts.[xviii] People of color are more likely to feel the economic downturns brought on by the pandemic due to various pre-existing economic disadvantages.[xix] The COVID-19 crisis is made worse for the people of color who may have no choice but to work on the frontlines. The following is a graphic on how Black populations in particular are at higher risk for COVID-19 due to the racial inequities that they experience.[xx]

Xenophobia makes the health crisis worse for people of color. For example, Black people face fears of discrimination for wearing masks,[xxi] Asian Americans face increased hate crimes,[xxii] and undocumented immigrants are not provided with the government’s stimulus checks,[xxiii] while tests or treatments of the coronavirus can put them at higher risk of deportation.[xxiv]

It is critical for the state government to integrate racial equity in emergency responses and recovery for this crisis, as well as for future emergency preparedness and responses. California state government must take action to shape the future for racial equity.

Part II: Recommendations

The author recommends:

- Establish a statewide Office of Equity.

- Expand and adjust CCORE to build groundwork for an Office of Equity.

Recommendation 1: Establish a Statewide Office of Equity

While other names may be considered (e.g. “Office of Racial Equity”), for the purposes of this report, the author will use the terms “Office of Equity” or “Office.” The Office will help to structuralize and embed racial equity in the entirety of the work of the state government, as well as center on the needs and desires of communities of color. Racism is an intersectional and structural issue — to dismantle it, an intersectional structure centering on the lived experiences of communities of color within state government is necessary.

The below information is based on interviews and a case study of the Washington state’s Office of Equity, which was signed into law in early April 2020 and is the first of its kind at a state government level. The author reviewed key documents and reports from the Washington State Office and conducted key informant interviews with one of the leaders connected to that effort.

Summary of Roles and Functions of a Statewide Office of Equity

- Coordinate racial equity work across the departments and agencies in California state government as a centralized office.

- Cultivate a shared understanding and definition of racial equity.

- Ensure incorporation of racial equity priorities and goals in strategic plans and incorporation of racial equity competencies in performance review metrics for staff.

- Provide training and workforce development.

- Conduct state-level community engagement.

- Communicate the goals and measured progress of racial equity work of the state government internally and externally.

- Employ a collaborative, non-punitive accountability and enforcement

How to Establish a Statewide Office of Equity

Possible Mechanisms of Establishment

Several mechanisms may be used to establish a statewide Office of Equity:

- Legislation placing the Office of Equity in the Governor’s Office will likely have the greatest impact. Legislation will signal the state government’s commitment to equity. This will embed and institutionalize racial equity at the cabinet level, implying that directors of state-level agencies will be evaluated on performance metrics related to racial equity. Legislation will also codify the Office of Equity. This will make it more difficult to undermine or dismantle the Office if a new administration does not support it. However, the process to secure legislation can take much time and resources and will require a legislator to sponsor it (bipartisan support is preferred). Success for the legislative approach will require racial equity champions in the Governor’s Office, the legislature, or ideally both, which may be difficult to acquire. In that regard, this mechanism may have lower feasibility, and the other three mechanisms could be explored.

- An executive order is a relatively simple and fast way to make immediate change if the governor supports the initiative. Gov. Newsom has already issued executive orders for several related actions, including establishing the office and position of the State Surgeon General in January 2019. However, an executive order may not have lasting impact as it may not carry weight with future governors. Furthermore, executive orders are generally unfunded.

- Nonprofit organizations, advocacy groups, and community-based organizations could present a proposal to be a part of the budget, with sponsorship from a legislator. If the Budget Act signed by the governor includes the proposal, then the proposal becomes part of the administration’s fiscal plan. This would fund the Office of Equity, but will require much coalition building including legislator sponsorship.

- Whether through the legislative or budget process, the Office could also be established within an existing agency like the Government Operations Agency (GovOps). This has been done before, but may not fund the Office of Equity.

Identify Funding Mechanisms

Despite current financial limitations, it is critical that an Office of Equity receives sufficient funds in order to ensure an equity lens across all of government’s key areas of work. The following are considerations for funding:

Given the all-of-government purpose and need for the Office of Equity, state General Funds should resource the Office, similar to departments such as the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR) and Department of Finance. However, the General Funds mechanism can be difficult, particularly with the COVID-19 emergency responses requiring much unplanned funds and the likely high unemployment rate in California next year resulting from the coronavirus pandemic.

Although not ideal, an Office of Equity could be created without any funding, with the intent to secure funding later. For example, the Office of Surgeon General was created without funding; it took almost a year for the Office of Surgeon General to identify resources for staffing, including some creative approaches that involve detailing staff from a number of interested departments including CDPH, Health and Human Services Agency, Department of Social Services, and Office of Planning and Research. Another example is the Office of Health Equity within CDPH and the Office of Equity within California Department of Social Services. Both of these offices have restricted funds tied to existing programs but no flexible funding for general equity work within their departments. If the Office of Equity follows this route, it will still face the challenge of identifying flexible funds to respond to the changing needs of departments across state government.

Key Considerations for Establishing an Office of Equity

The following are recommended considerations to take when creating a statewide Office of Equity, based on interviews and the Washington Office of Equity case study. In order to achieve racial equity, the California statewide Office of Equity must consider the following and center on the needs, wants, and suggestions from the communities, especially those of color. The below will also strengthen the aforementioned roles and functions of the Office of Equity:

- The Office of Equity must strive not just to treat symptoms, but address the root causes of racial inequities, which entails deeply engaging with communities. Using a nuanced approach to data collection, analysis, and application and working across a wide range of sectors and policy issues are necessary.

- Community engagement must shape, be a function of, and inform the work of the Office of Equity. Community engagement must be done with respect and cultural humility. Communities know their lived experiences, struggles, and solutions the best; the government cannot make assumptions on what these are.

- The Office of Equity should value, use, and be informed by data, storytelling, and lived experiences. It is important to undertake a values-driven approach rather than an evidence-based approach as data may not fully and accurately capture the experiences of the communities of color and may marginalize and oppress communities further. Data should still inform but not drive decision-making. Storytelling can be powerful to help government employees understand their role and responsibility in the racial inequities that are reflected by the data and lived experiences.

- The Office of Equity should ensure a healing-centered approach for addressing and healing from internalized biases and oppression for both communities and the state government employees conducting the racial equity work. To strive towards racial equity and help marginalized and oppressed communities heal, the state government itself needs to embody a healing-centered approach, especially as many employees themselves have experienced trauma in their work. There needs to be a culture of openness and acceptance for vulnerability among state government employees and with communities.

- The goal, mission, vision, principles, roles, and responsibilities of the Office of Equity must be as specific as possible and driven by values from the communities. The associated risks, potential obstacles, gaps, and assumptions in the execution of the Office should also be considered.

- The authority of the Office of Equity must be clearly established, and the Office should have convening authority (i.e. the ability to convene high-level staff). The Office should still have convening authority even if every department or agency do not have staff dedicated full-time to racial equity work.

- The resources necessary for the Office of Equity must be identified, and the Office must secure sufficient resources such that its work will not be undermined nor siloed. Relatedly, the durability and scale of the Office of Equity must be considered as the Office would take much resources and funding, especially given the economic situations resulting from the COVID-19 crisis.

- There should be liaisons in every department and agency who serve as a point of communication between their department or agency and the Office of Equity. Ideally, each department and agency will have their own Office of Equity, similar to the CDPH’s Office of Health Equity. If it’s not feasible to establish an Office of Equity in every department and agency, there should at least be staff who are dedicated to this role to allow coordination, input, and responsibility of the department or agency. For example, the Washington Office of Equity will have Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion liaisons. These liaisons are needed because the statewide Office of Equity will not be able to provide technical assistance at the detailed level of, for example, one department’s approach to community engagement.

- The Office of Equity should be established alongside a legislative mandate for departments and agencies to integrate racial equity in their strategic plans, and the Office will ensure that the departments and agencies are integrating racial equity in strategic plans.

- When racial equity is embedded in every employee’s work, the output, outcomes, and employee performance of the racial equity work must be thoughtfully measured. The measurement must incorporate a racial equity lens. Staff from CalHR and labor unions must be a part of this conversation.

- The Office of Equity must measure its own progress and report to the Governor and/or legislature on its progress. This implies that the Office must establish and measure its yearly goals and targets. An annual written report could be one approach, which should be also available for public access and input.

- The enforcement and accountability mechanisms of the racial equity work mandated by the Office of Equity must be thoughtfully and considerably done. Between a “carrot” (i.e. reward to induce racial equity work being conducted) and “stick” (i.e. punishment to prevent the lack of progress on racial equity work) approach, the Office should take on the “carrot” approach. The “stick” approach may result in inauthentic racial equity work, as departments and agencies may feel forced to do it; an example of a “stick” approach is withholding funding if a department/agency falls behind on its racial equity work. With the transparency, sufficient resources, and government-wide support for the racial equity work as a “carrot” approach, departments and agencies will be motivated and encouraged to collaborate towards accountability.

- The Office of Equity should consider building coalitions with other state governments to advance racial equity nationwide.

- The Office of Equity should consider technological fixes that can help reduce the current additional workload from racial equity work, such as anonymizing applications to state government job openings by hand.

- If a statewide Office of Equity is not deemed to be the appropriate approach to take, then institutionalization of racial equity must still occu Other options may be to have at least liaisons across the state government or creating a new function in, for example, the Governor’s Office or GovOps.

Early Action: Establish an Office of Equity Committee

While it will take time to establish an Office of Equity, a Committee that will begin planning and pursuing the Office can and should be launched now:

- Liaisons from departments and agencies should partake in the Committee. These liaisons can begin to identify areas to incorporate racial equity in their department or agency before the Office of Equity is established and communicate with each other.

- The Committee can highlight the data and lived experiences of the systemic racial inequities, especially prevalent and worsened in the time of the coronavirus global pandemic, to make the need for the Office of Equity more transparent.

- Existing state government employees who may already have been conducting community engagement on the field in offices statewide should participate in the Committee. They can serve as the trusted messengers and communicators between the state government and communities in these times, as they have already established some relationships with the communities before the shelter-in-place orders.

- A Committee launched now will create infrastructure before the establishment of the Office, and, in the less preferable scenario that the Office is not created, this infrastructure can still last.

Next Steps, in the Context of a Constrained Budget

In the present, incremental steps need to be taken towards creating an Office of Equity, largely due to the impacts on budget and available funding from the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis. It is imperative that budget constraints do not derail the racial equity work that is so critical for the mission of state government and well-being of all Californians, including during this global pandemic.

In the current context of a constrained budget, as mentioned above, the CCORE program should be adjusted and expanded in order to continue the culture of support for racial equity and create momentum for establishing the Office of Equity.

With the ongoing pandemic, it is becoming increasingly evident that racial equity must be pursued, particularly in emergency preparedness and response and healthcare. The current administration has already shown interest and investment in equity through different task forces (e.g. diversity and inclusion task force); increased translations of government resources especially during the COVID-19 crisis; creating an accommodating, inclusive workspace, etc. By centering and institutionalizing racial equity, the Office of Equity will allow Gov. Newsom’s administration to move closer to achieving its “California for All” mission.

Recommendation 2: Expand and Adjust CCORE to Build Groundwork for an Office of Equity

While establishment of an Office of Equity will take time, California state government should continue to build its racial equity capacity and commitments by expanding and adjusting CCORE to reach more departments and increase transparency and accountability. More departments and agencies are participating or showing interest in participating in the program in 2020, indicating a growing commitment to racial equity and an increased awareness of the program itself and its benefits. As an enterprise-wide system of connections, CCORE will continue to build a culture of support and momentum that will ultimately help with the establishment and launch of a statewide Office of Equity.

Quotes from GARE Capitol Cohort and CCORE Participants, Between 2018-2020

The following participant quotes were gathered through surveys and interviews.

One of the Cohort’s greatest contributions is its power to motivate State workers and nurture our efforts.

The Cohort has connected me with an incredible network of passionate and brilliant CA civil servants and broken down silos across agencies/departments.

GARE has made the discussion of racial equity very public and created a new area of focus for policies and procedures going forward.

The Cohort has signaled to our executive leadership that there are important structural and policy changes that need to be made.

CCORE has provided institutional authority for me to do work explicitly relating to racial equity.

The Cohort has created a vocal team within the department to start communicating the importance of these concepts to a larger audience.

GARE has made me more conscious of the impact I personally can have to create positive outcomes.

Because of participation in the Capitol Cohort, we can be honest about how our office is not as equitable as it thinks itself to be.

GARE has helped us see our role as government in creating a more equitable future for Californians.

I felt like I already had a good understanding of all the factors that gave rise to [racial inequity], but I realized it really has not gone deep enough. Exposure to [CCORE] really deepened my understanding. It brought home this idea of using an equity lens, and helped me get in touch with my personal and professional experiences as a woman of color in a government setting.… Personally, it’s helped me be more comfortable understanding and in turn communicating it.

Our department is finally starting to see that we need to look at how we serve people better. Equity is a huge part of that conversation.

I’ve always said, a tool is only going to be good as the person using it. You’re asking the question about who’s going to be impacted [but] you may not have the training to think about these populations. I think [the shared understanding and training] is a prerequisite.

Being in the Capitol Cohort gave [my team] a lot of capacity and tools to be ambassadors within our own agency.

The CCORE program is so valuable because it takes you through a series of step-by-step processes to evaluate what you can achieve within your own department or agency and then really work to incorporate equity into policy and business-as-usual.

One of the benefits [of CCORE] is partnering with other agencies when possible and being open about sharing resources with each other and sharing each other as a resource.

I think most people come and talk to each other about their programs and work that is very specifically statutorily required. Often times, the way that those statutes are created does not allow for equity conversations. CCORE is creating the space to have those conversations. I think fundamentally, that’s the biggest, most important thing.

CCORE brings state level partners together, creating a safe place where we can have the hard conversations and support each other to learn and grow…. Having space where we’re able to connect both on a personal and professional level on a specific topic like racial equity, there’s a tangible value in terms of building camaraderie, feeling like you’re not isolated.

Recommended Adjustments to CCORE

In response to the limitations discussed above, the following are recommended adjustments to increase accountability and implementation impact by participating departments:

1. The Governor’s Office should explicitly state support for racial equity work, including CCORE. Participating departments and agencies should share their Racial Equity Action Plans (REAPS) with the Governor’s Office. This is critical for ensuring a “permissive atmosphere” to tackle racial inequities and supporting department leaders to secure the staff capacity and resources necessary to publish and implement the REAPs. Several informants voiced a desire for vocalized, explicit support and commitment similar to Governor Newsom’s Executive Order that issues an apology to Native Americans for the state government’s “violence, exploitation, dispossession and the attempted destruction of tribal communities” throughout history.[xxv]

2. CCORE should set clear expectations at the start of the program that REAPs are accountability tools and should eventually be published online. The program should include flexibility on when and how the plans will be published. Some departments and agencies that have never done racial equity work prior to participating in CCORE may benefit from starting off with an internal-only REAP, but should still move in the direction of public transparency.

CCORE participants at CDPH noted that having CDPH’s initial REAP be an internal document allowed more time to gain support from upper management. Because the initial REAP was not public, it also was easier to embrace a bigger vision than would have been possible under public scrutiny. In departments where executive leadership is not driving the work, beginning with an internal REAP may allow for the racial equity work to be undertaken in some parts while support is built. Alternatively, departments and agencies may create separate internal and external versions.

3. Participating department and agencies should deploy strategies to build collective staff commitments to racial equity activities in the REAPs as racial equity work cannot be siloed to a few people. Improving the implementation of REAPs requires increased staff capacity, along with budget, time, and resources. As this work requires significant changes within institutions, the work to advance racial equity should not be limited to a small group of people or even a single person. It should not be considered extracurricular, optional work that is additional to existing work, either. More staff can commit to implementation of REAPs through effective storytelling with data as well as increased communication on racial equity work across departments and agencies.

4. Storytelling with data and increased communication on racial equity work within the state government will increase staff commitment to racial equity work. This will allow staff to see their role and responsibility in prioritizing racial equity and encourage a “friendly competition and collaboration” among departments and agencies to advance racial equity, as one interviewee described.

5. As departments and agencies develop and implement their REAPs, they should receive additional tailored, technical assistance. Although this may be challenging due to how resource intensive the assistance may be, the program would benefit from additional customized technical support to participating departments. CCORE is funded through training contracts, which limit technical assistance and other non-training activities. Other funding mechanisms should be explored to expand the type of technical assistance and support that can be provided, in addition to training itself.

“You need a lot of one-on-one coaching and consultation and working with people to really figure out how to navigate these very complex systems and make things happen. I don’t think there’s a cookie cutter approach to be able do that; that’s a lot of rolling up your sleeves and getting dirty and [it’s] super resource intensive. To be able to go deep, you need that expertise, time, and those resources, and [they’re] the hardest thing to have.”

-Meredith Lee, HiAP Team Lead of CDPH

6. CCORE should employ greater communications with stakeholder groups including the public, publicly demonstrating the state’s commitment to racial equity and inviting input on REAPs from the communities of color most impacted by racial inequities. An annual public briefing from CCORE may be one approach to this. One example of stakeholders is PHI’s HiAP external stakeholder group, which provides input to HiAP programming including CCORE, and at times has attended and advocated for health and racial equity at state agencies’ public meetings.

Several CCORE participants have expressed that this would be helpful, with clear, transparent communication and collaboration between stakeholders and departments and agencies. Without such communication, state departments and agencies may feel undermined by the stakeholders or taken by surprise from stakeholders’ input. It should be noted that PHI’s existing external stakeholder group is “grasstops,” i.e. consists of people who run organizations that provide services, not the people who receive the services themselves. This should not substitute for direct engagement with communities.

Similar to how each department and agency will need tailored technical assistance, each department and agency should have different accountability structures that are context specific. These will depend on the size of the department, the support from staff in positional authority, types of stakeholders, etc. It will also be important to provide CCORE departments and agencies with coaching and support for meaningful stakeholder engagement, so that the engagement can be effective and supportive of both community stakeholder goals and the ability of staff to succeed.

7. CCORE should collect more impact stories from participating departments and agencies and communicate them out strategically to the enterprise to increase awareness of the program and its benefits. Currently, anecdotes about impacts are shared in an ad hoc nature.

Holly Nickel, Racial Equity Strategist at PHI said, “As CCORE departments continue to implement their REAPs, it’ll be imperative to the enterprise that we share out stories. Gathering challenges, successes, lessons learned and sharing them out will only help grow the understanding that government has a role in addressing institutional racism and can do so concretely. These stories will, I hope, create the ‘aha moment’ that transformation is possible and that we can begin to see the starts of transformation in a relatively short timeframe.”

8. CCORE should partner with CalHR to pursue workforce equity together, such as providing clarifications on Proposition 209 and integrating racial equity in trainings offered by CalHR. Departments look to CalHR for guidance on what is allowed with regard to workforce racial equity, and if CalHR does not provide specific guidance on how to do focused recruitment or other equity strategies, departmental staff often interpret that lack of guidance as lack of support.

Additional recommendations on opportunities to partner with CalHR can be found in the 2018 report “Racial and Gender Pay Gaps in California State Government: A Path Towards Workforce Equity.[xxvi]”

Benefits of CCORE

Interviews with several CCORE participants and staff revealed the following benefits.

- Participation has helped participants better articulate issues or experiences related to racial inequities, as well as understand them on a deeper, more personal level.

- CCORE allows participants to nurture a shared definition and understanding of racial equity and prioritization of racial equity, which are currently lacking in not only California state government, as mentioned earlier, but also across the nation. It has also led to participants reading more and continuing to understand how their department or agency has been playing a role in creating and perpetuating racial disparities.

- CCORE gives individual participants the capacity and tools for leadership in advancing racial equity in their work. Another informant shared an observation of the application of a racial equity lens thanks to training from CCORE: With the COVID-19 crisis, their colleague advocated for postponing certain decision-making processes and not using webinars as a substitute for public meetings, given that many may not have reliable access to such technology or internet.

- Most notable of the tools is the REAP, which is a policy tool that did not exist in California state departments and agencies before CCORE. A participant explicitly credited their participation in CCORE for the ability to quickly respond to language access needs in this time of the COVID-19 crisis; the department/agency had already included language access as a priority in its REAP prior to the crisis.

- CCORE allows for connections and collaboration among not only staff within the same department or agency (especially if said department of agency has many staff), but also different departments and agencies. As a result, resources can be shared among participants, within the same department or agency, or across departments and agencies. Program participation also creates opportunity for innovation and program and policy development.

- Perhaps most importantly, however, CCORE creates space for conversations on race, racism, and racial equity and normalizes these conversations. Some interviewees noted that even to begin the conversations on race and equity is especially a win for departments that have a large number of staff and traditionally less focused on measuring populations in outcomes.

- Through all of this, CCORE provides racial equity capacity building and technical assistance to departments across the enterprise. It is also building up interest and participation to cause a tipping point for racial equity in state government. Holly Nickel, Racial Equity Strategist of PHI, noted that the program has been increasingly acknowledged for how it can be used to meet some of the governor’s priorities in his “California for All” mission and his task forces: “We’re creating political will at the enterprise level, adding more participating departments to cause a tipping point for the enterprise to prioritize and concretely advance racial equity.”

Limitations of CCORE

Interviews with CCORE participants and staff provided the following list of challenges:

Individual CCORE participants face barriers to full engagement – preventing them from making the most of the program and limiting the effectiveness of the program. These barriers would apply to any voluntary capacity building program, and include the lack of participation from upper management staff; lack of staff capacity and resources; lack of a shared understanding of racial equity and discomfort with racial equity work; and racial equity not built into job descriptions, making it conflict with other priorities.

CCORE also faces barriers of participation related to cost and travel. Some departments and agencies may find it difficult to secure the funds to pay for participation. In addition, some departments and agencies may find it difficult to physically participate in in-person trainings in Sacramento, especially if the entity has staff working across the state of California.

Similar to state departments and agencies, PHI and partners that facilitate CCORE face limitations in funding, resources, and time. PHI not only provides training through CCORE, but also conducts a multitude of “behind-the-scenes” work in service of the CCORE teams and for advancing racial equity within the state government. For example, staff engages with executive level staff to promote REAPs and lessons learned to amplify the importance of racial equity and soften the ground for future discussions. Staff organizes and convenes key partners and stakeholders to advance racial equity across the enterprise. To conduct such support and strategy work, PHI needs to secure funding, which is separate from the funding provided to the training and takes time.

Most notable among the challenges is that CCORE relies upon voluntary action, which can limit accountability and impact. State government employees may be reluctant to conduct the racial equity work because of the challenges in the implementation of the REAPs. With CCORE being voluntary, they may not be motivated to conduct the work. However, implementation is challenging for all types of racial equity work, especially on the enterprise level; that does not excuse one from responsibility nor accountability. The challenges are not easily resolved by merely adding more training, materials, tools, etc.

“There’s no silver bullet for racial equity implementation. California as a state is on the cutting edge in doing racial equity training and consultation at such a big scope multi-sectorally and across so many departments. That’s just the nature of the beast. Advancing racial equity is already difficult, but then you add the scope and it becomes more difficult. Tools, materials, and training are of course helpful, but if we don’t take action, time, and spend resources to apply them in our work, they don’t mean anything.”

-Holly Nickel, Racial Equity Strategist of PHI

Most departments have not shared their REAPs publicly. While several departments have publicly announced their CCORE participation through newsletters and other communications, only one has been published to the public.[xxvii] Some REAPs have been shared across their departments, but others are not internally public, i.e. not released to the entire staff of the department or agency. Departments have cited challenges including limited staff capacity, limited communications (both between CCORE teams and executive level staff and among peer executive level staff), lack of resources, and lack of support from upper management staff on the creation and implementation of REAPs.

Specifically, staff in positional authority may hesitate to publicize the REAPs because the department or agency does not want to make promises that will not be followed through due to lack of staff capacity and resources. Alternatively, the REAP may not contain “bold enough” goals to be published. One participant noted that when creating and implementing a REAP, it is difficult to strike a balance in the REAP between having a bold vision and having feasible planned actions with the given, limited resources. Furthermore, some departments and agencies are not comfortable with publishing their REAPs unless there is explicit support and commitment from the highest level of management, i.e. they won’t release it unless they have clear direction from their cabinet secretary or Gov. Newsom.

Some departments additionally shared that a challenge in creating the REAP was the change of templates from Year 1 to Year 2, requiring additional work to update. Several informants noted that both templates were not necessarily easy to understand and did not match the structure, design, and format of their existing work documents, making the REAP a separate document from the department or agencies’ other documents.

Part III: Conclusion

Years of history already show that failing to advance racial equity leaves people of color vulnerable. Racial equity has always been important and should be a priority for all staff working within California state government. The state government has been making impressive progress with CCORE. Continuing the CCORE with expansion and adjustments will create momentum for a statewide Office of Equity, and the Office will allow for racial equity to be embedded in all functions and operations of California state government. The Office will establish the intersectional structure that will center on communities of color and institutionalize racial equity, contributing to dismantling the structural racism in this state and in this country.

With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the present is a critical time to advance racial equity when structural racism combined with the coronavirus leave hundreds of people of color increasingly vulnerable.

“If we did further research post-COVID-19 and find that racial inequity contributed to some of the challenges we had, do we agree that we’re not going to tolerate it anymore and do something about it? Do enough people stand up with a strong enough voice to say no more?… We cannot give lip service to [racial equity] anymore, we really have to attack [inequity] as a government, as a society.”

-Kathleen Webb, Chief Deputy Director of California Department of Motor Vehicles

California state government has a mission to serve all Californians. It cannot return to operate as it did before the coronavirus outbreak without prioritization for racial equity. Now more than ever, racial equity is a must, not a maybe.

Appendix: Washington Statewide Office of Equity Case Study

The Washington state government established the nation’s first Office of Equity at the state government level. At the time of this report, it is the only statewide Office of Equity across the nation. The following case study on Washington’s statewide Office of Equity is based on interviews with Christy Curwick-Hoff, Manager of the Washington state Governor’s Interagency Council on Health Disparities. Curwick-Hoff provides oversight and supervises the staff of the Washington state Office of Equity Task Force.

History of Washington State Government’s Racial Equity Efforts

Although the Office of Equity was established in 2020, its history goes back almost 15 years and has its roots in the social determinants of health and health equity. In 2006, the Washington state legislature created the governor’s Interagency Council on Health Disparities based on a recommendation from the 2005 joint legislative committee on health disparities. The Council consists of health and non-health agencies and focuses on social determinants of health. As the Council continued conversations with different advisory committees, a theme consistently prevailed.

“[The Interagency Council] kept hearing the same thing: We’re never going to be able to eliminate those inequities in health…until we can really address the systematic inequity that exists across all of our systems.”

-Christy Curwick-Hoff, Manager of the Interagency Council

Washington’s Interagency Council on Health Disparities began its equity work in 2010-2012 by focusing on language access. The Council presented recommendations to the governor on standardizing the delivery of language access services and ensuring that the agencies’ language access responsibilities were fulfilled. To do so, the Council recommended a language access policy and plan across all agencies, a language access coordinator, and a central coordinating agency.[xxviii]

Inspired by King County’s Equity and Social Justice Initiative and the City of Seattle’s Race and Social Justice Initiative, the Council then sought a statewide equity initiative. The Council presented recommendations to the governor in 2015, outlining 10 areas of focus and three key themes. The first theme was workforce equity to reflect the diversity of the state, increase the cultural humility of the workforce, and ensure respectful and inclusive workplaces. The second theme was service delivery, ensuring language access and conducting equity impact analyses as well as providing services fully and equitably to communities. This includes community engagement. The third theme was systems changes, examining how the systems, policies, and processes in the state government had been marginalizing communities and what changes would be necessary to pursue equity.[xxix]

The Road to Establishing Washington state’s Office of Equity

While in continuous conversation with the governor, the Council and the Governor’s Office began to discuss an executive order to implement the aforementioned recommendations as a statewide equity initiative. At the same time, several legislators were having similar conversations with their constituents. The legislators reached out to the Council in 2018, which shifted the conversation from creating an executive order for a statewide equity initiative to creating a statewide Office of Equity through legislation. The legislative approach was preferred as the Office would be in statute and codified.

Curwick-Hoff advised that “[i]f you know there’s a viable pathway towards [establishing the Office of Equity through legislation] and you feel like you have champions and votes, then certainly go that direction.”

Legislation for the Office of Equity was first introduced in the 2019 legislative session by a House Representative and a Senator. A core team consisting of members in the legislature, Governor’s Office, and various commissions contributed to create the legislative proposal with technical assistance provided by Curwick-Hoff. The legislation aimed to officially start the Office on July 1, 2019. The Office of Equity was planned to be situated within the Governor’s Office, with positional authority to ensure that racial equity is embedded in all programs and hold accountable the executive branch agencies, particularly those cabinet agencies that report to the governor. Additionally, the Office of Equity needed funding, and the governor had already included $1 million for the Office when they introduced their proposed budget before the beginning of the 2019 legislative session.

However, the bill did not pass in 2019. When the legislators knew the bill would not pass during the legislative session, they strove to fund a proviso instead. Through this mechanism, the Council received funding to create the Office of Equity Task Force, which began in July 2019. The Task Force delivered preliminary recommendations to the governor in December 2019[xxx] based on conversations with stakeholders and centering community engagement in their recommendations (see more on community engagement below). The Task Force’s final recommendations are forthcoming as of this memo.

The bill did pass the 2020 legislative session in both the House and Senate, and the governor signed the Office of Equity into law in early April 2020. The Office received $1.2 million from the state government’s operating budget. However, due to the economic conditions brought by the COVID-19 crisis, the funding will not be immediately available to the office, so the Office of Equity was officially established on July 1, 2020 within the Governor’s Office, without funding.

The Washington Office of Equity Task Force’s Recommendations to Its Governor

Below are excerpts from the Office of Equity Task Force’s December 2019 summary recommendations to the governor.[xxxi] The content of this section are direct quotes from the summary recommendations. Many of the recommendations are informed through community engagement.

Definition of Equity:

Developing, strengthening, and supporting policies and procedures that distribute and prioritize resources to those who have been historically and currently marginalized, including tribes. It requires the elimination of systemic barriers that have been deeply entrenched in systems of inequality and oppression. Equity achieves procedural and outcome fairness, promoting dignity, honor, and respect for all people.

Guiding Statements for the Office of Equity:

Vision

Everyone in Washington has full access to the opportunities, power, and resources they need to flourish and achieve their full potential.

Mission

The Office of Equity will promote access to equitable opportunities and resources that reduce disparities and improve outcomes statewide across government.

Recommended Roles for the Washington State Office of Equity:

- Guide enterprise-wide efforts through a unified vision of equity

- Serve as a conduit between government and communities

- Serve as a conduit for state institutions

- Provide guidance and technical assistance to foster systems and policy change

- Set expectations and measure progress

- Ensure accountability and enforcement

- Reconvene the Task Force to evaluate the state’s implementation of an Office of Equity, including the level of funding provided for its operation; and review the Office’s progress and recommend any needed changes to its operation and strategies

Lessons Learned from the Office of Equity Task Force’s Work

There are several lessons learned from the Office of Equity Task Force’s journey to establishing the Office.

- It is critical to find the necessary support and buy-in within the state government. The Task Force’s work was enabled thanks to having a champion for the racial equity work in the Governor’s Office; a governor who held equity as a priority; the same administration when the idea of a statewide equity initiative was discussed and when eventually the Office of Equity was set in motion; the legislators who provided bipartisan support to the Office and sought funding for the Task Force when the first bill did not pass; and the leadership of the Task Force who were already deeply rooted in their communities prior to the Task Force and upheld the values-driven approach advocated by communities, as well as extremely knowledgeable and comfortable to facilitate conversations on race.

- Those who have already been conducting the racial equity work must join the conversations as thought partners and help shape the Office of Equity, as they will continue to execute the racial equity work. In the Washington state government, several racial ethnic commissions as well as other agencies and groups have already been conducting racial equity work. It was important to clarify with them that the Office would not take over existing racial equity work, but rather coordinate it.

- Conversations with key partners and communities are critical for shaping the Office of Equity. The Task Force allowed members to collaborate with stakeholders and community members on further shaping the mission, goals, and responsibilities of the Office. Moreover, the Task Force had the opportunity to engage with communities and center its recommendations on communities’ wants and needs. “We were kind of putting the cart before the horse with the 2019 legislation by standing up the office and taking a couple of months of work to figure out what that should look like,” Curwick-Hoff shared. “When the bill didn’t pass last year, that was a really great opportunity for us to get all of these partners together and work together to figure out how this office is going to help us coordinate, support, and elevate the work that’s going on in the state and not supplant that and take it over…. That was super helpful.”

- The quick pace of the Task Force was a limiting factor for the Task Force. Curwick-Hoff noted that “we were able to have a year to do [community and stakeholder engagement] in the Task Force. But even that was not enough time. The pace of that Task Force was so fast it was hard for us to get all of our key partners on the same page. The pace of the Task Force was not helpful enough to be able to do that.” This was especially the case for community engagement, as the fast pace limited the robustness of the engagement. The Task Force opted to have robust recommendations in the December 2019 report to inform the 2020 legislative session in lieu of more robust community engagement.

- Requesting the right amount of funding for the Task Force’s community engagement in the 2019 legislative session was difficult. The money was needed to fund effective engagement, but it also needed to be reasonable enough that the funding would be granted. “When being asked to put forward a fiscal note, you really have to balance asking for what you want to do the work well with a reasonable amount,” Curwick-Hoff said. “You want to do the work and move this forward, so you don’t want to ask too much money, but you also want to ask for enough money so you can do it effectively.” It was also difficult because this state-level community engagement is not traditionally funded in the way that the Task Force sought.

- The Task Force was able to secure a Community Engagement Coordinator who bridged between the communities and the Task Force. In addition to online surveys and community forums, the Coordinator directly met community members on the ground, ensuring that the meetings were inclusive and allowed participants to have a voice rather than given a set amount of a public comment period. The Coordinator met and conversed with community members before meetings to inform them of the meetings and invite them. If some community members were not able or did not feel comfortable to join, the Coordinator shared their thoughts and opinions in the meetings on their behalf.

- Leading the work with values based on community engagement is incredibly important. The Task Force started its conversations with operating principles on centering race and community, based on the Interagency Council’s own principles. It was crucial to normalize conversations about race, racism, and racial equity, as well as intersectionality and the inequities in all marginalized communities. The Task Force held many discussions on data sovereignty and evidence-based practices, along with how the evidence is based on the majority populations and may not capture fully and accurately the lived experiences of marginalized populations. As the 2019 report advises: “Avoid letting data drive the work—be driven by vision and informed by data.”[xxxii] Re-emphasizing the importance of facilitators and leaders of all these conversations, Curwick-Hoff shared: “We talked a lot about vulnerability and being open in our Task Force and the need to not wear the hat of our agency or organization to the table, but bringing our whole selves and our lived experiences to the table.”

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the privilege to be able to work and research indoors, as millions of people across the nation—especially people of color—are facing numerous vulnerabilities due to the coronavirus crisis and do not have the same privilege. Many among them are not even able to think about a future after the global pandemic. It is the author’s hope that this report will assist California’s state government so that it can fully and equitably serve and help all Californians, especially when such disasters strike.

The author thanks the following key interviewees and stakeholders. This report would not have been made possible without their time and support for the research.

Research Mentors/Sponsors

Julia Caplan*, Public Health Institute, Meredith Lee*, California Department of Public Health

Key Informants

Artnecia Ramirez, California Department of Public Health, Ashley Horne, Race Forward/Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE), Christy Curwick-Hoff, Washington State Government, Dwayne Marsh, Race Forward/GARE (formerly), Evette Jasper, Washington State Government, Glenna Wheeler, California Department of Human Resources, Holly Nickel*, Public Health Institute, Dr. Janice Underwood, Virginia State Government, Jeanie Ward-Waller, California Department of Transportation, Jessica (Jessie) Buendia, Strategic Growth Council, Julie Nelson, Race Forward/GARE, Kathleen Webb, California Department of Motor Vehicles, Lazaro Cardenas*, California Department of Public Health, Leslie Zeitler, Race Forward/GARE, Lianne Dillon*, Public Health Institute, Dr. Louise Bedsworth, Strategic Growth Council, Dr. Raintry Salk, Race Forward/GARE, Sarah Gessler, California Department of Human Resources, Steve Lee, Oregon State Government, Sumi Selvaraj, California Coastal Commission, Suzanne Hague, California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, Yesenia Murillo, Michigan State Government, Three anonymous interviewees

* Asterisk indicates staff to the California Health in All Policies Task Force.

Graduate Advisor: Dr. Candace Hester-Hamilton, Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley

Lastly, the author expresses her deep gratitude to her family and friends for their continuous support, especially in unprecedented times.

List of Acronyms

| Acronym | Full Term/Title |

| CalHR | California Department of Human Resources |

| CCORE | Capitol Collaborative on Race & Equity |

| CDPH | California Department of Public Health |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus |

| GARE | Government Alliance on Race and Equity |

| GovOps | Government Operations Agency |

| HiAP | Health in All Policies |

| PHI | Public Health Institute |

| REAP | Racial Equity Action Plan |

Endnotes

[i] Bardach, E. and Eric Patashnik. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving. CQ Press, 2015.

[ii] Blakemore, E. “California Once Tried to Ban Black People.” History.com. February 9, 2018. Updated September 1, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/california-once-tried-to-ban-black-people.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Studythepast.com. “Jim Crow Laws: California.” Accessed on April 27, 2020. https://www.studythepast.com/weekly/cacrow.html.

[v] Florido, A. “Mass Deportation May Sound Unlikely, But It’s Happened Before.” NPR Code Switch. September 8, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/09/08/437579834/mass-deportation-may-sound-unlikely-but-its-happened-before.

[vi] Green, M. “How Government Redlining Maps Pushed Segregation in California Cities.” KQED. April 27, 2016. https://www.kqed.org/lowdown/18486/redlining.

[vii] Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Japanese American internment.” Accessed on April 27, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/event/Japanese-American-internment.

[viii] Stanford Law School. “Three Strikes Basics.” Accessed on May 7, 2020. https://law.stanford.edu/stanford-justice-advocacy-project/three-strikes-basics/.

[ix] Moore, E. and Gerald Lenoir. “The California Story: The Structural Forces Behind Our Racial and Economic Inequality.” UC Berkeley Othering & Belonging Institute. April 18, 2018. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/california-story.

[x] Mathew, T. “Mapping Racial Disparities in the Golden State.” CityLab. November 21, 2017. https://www.citylab.com/equity/2017/11/mapping-racial-disparities-in-the-golden-state/546149/.

[xi] California Health in All Policies Task Force. “Equity in Government Practices Action Plan.” Endorsed by the California Strategic Growth Council (SGC) on January 29, 2018. http://sgc.ca.gov/programs/hiap/docs/20180201-HiAP_Equity_in_Government_Practices_Action_Plan_2018-2020.pdf.

[xii] PolicyLink. “The Equity Manifesto.” Accessed on April 27, 2020. https://www.policylink.org/about-us/equity-manifesto.

[xiii] Executive Department, State of California. “Executive Order N-15-19.” June 18, 2019. https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/6.18.19-Executive-Order.pdf.

[xiv] Office of Gov. Gavin Newsom. “Governor Newsom Proposes 2019-20 ‘California For All’ State Budget.” https://www.gov.ca.gov/2019/01/10/governor-newsom-proposes-2019-20-california.

[xv] SGC. “Health in All Policies.” Accessed on April 27, 2020. http://sgc.ca.gov/programs/hiap/.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Kendi, I.X. “What the Racial Data Show: The Pandemic seems to be hitting people of color the hardest.” The Atlantic. April 6, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/coronavirus-exposing-our-racial-divides/609526/.

[xviii] Poston, B. et al. “Younger blacks and Latinos are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates in California.” The Los Angeles Times. April 25, 2020. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-04-25/coronavirus-takes-a-larger-toll-on-younger-african-americans-and-latinos-in-california.

[xix] Maxwell, C. and Danyelle Solomon. “The Economic Fallout of the Coronavirus for People of Color.” Center for American Progress. April 14, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/news/2020/04/14/483125/economic-fallout-coronavirus-people-color/.

[xx] Coke, D. “Why COVID-19 is Ravaging Black America.” Instagram @ohhappydani. April 15, 2020. Accessed on April 23, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/B_AzK35FhJ7/.

[xxi] Young, D. “Masking while black: A coronavirus story.” The Washington Post. April 10, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/04/10/coronavirus-masks-black-america/.

[xxii] Martinez, M. “California study tracks hate crimes against Asian Americans amid COVID-19 outbreak.” KCRA3, NBC. April 10, 2020. https://www.kcra.com/article/california-study-tracks-hate-crimes-against-asian-americans-amid-covid-19-outbreak/32100956.

[xxiii] Lantry, L. “What it’s like bring undocumented during the novel coronavirus.” ABC News. April 8, 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/undocumented-coronavirus/story?id=69840618.

[xxiv] Kendi, I.X.

[xxv] Executive Department, State of California. “Executive Order N-15-19.”

[xxvi] Qazi, H., “Racial and Gender Pay Gaps in California State Government: A Path Towards Workforce Equity.” July 2018. https://sgc.ca.gov/programs/hiap/docs/20180719-Racial_and_Gender_Pay_Gaps_in_California_State_Government_A_Path_Towards_Workforce_Equity.pdf

[xxvii] SGC. “Strategic Growth Council Action Plan (2019).”

[xxviii] Washington Governor’s Interagency Council on Health Disparities. “June 2014 Update: Action Plan to Eliminate Health Disparities.” June 2014. https://healthequity.wa.gov/Portals/9/Doc/Publications/Reports/HDC-Reports-July-2014-ActionPlan.pdf.

[xxix] Washington Governor’s Interagency Council on Health Disparities. “June 2016 Update: State Action Plan to Eliminate Health Disparities.” June 2016. https://healthequity.wa.gov/Portals/9/Doc/Publications/Reports/HDC_June2016ActionPlanUpdateReportFINAL.pdf.

[xxx] Washington Office of Equity Task Force. “Preliminary Report to the Governor and the Legislator.” December 2019. https://healthequity.wa.gov/Portals/9/Doc/Task%20Force%20Meetings/Equity%20Office%20Task%20Force%20-%20Preliminary%20Report%20(final)%20(002).pdf.

[xxxi] Washington Office of Equity Task Force. “Equity Office Task Force: Creating an Operations Plan for a WA State Office of Equity.” December 2019. https://healthequity.wa.gov/Portals/9/Doc/Task%20Force%20Meetings/Equity%20Office%20TF%20-%20Summary%20Recommendations%20(Jan%202020).pdf.

[xxxii] Washington Office of Equity Task Force. “Preliminary Report to the Governor and the Legislator.” Page 24.

Disclaimer: The author produced this report as her Spring 2020 capstone project for the Master of Public Program at the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley. The recommendations and conclusions are solely those of the author and do not represent views from the Goldman School of Public Policy, Health in All Policies Task Force, Public Health Institute, or the government employees and others who served as interviewees for this project.

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.